When will English speak to all the Englishes?

Black English, Indian English, Hinglish and Singlish, all have different relationships to Standard English and Globish. What’s a unifying way to think about them?

If you grew up in a country that fought the British Empire for its freedom, like Kenya, India, the USA or a few dozen others, you know that some or many of your compatriots have a strained relationship with its language, this language that you’re reading now. We don’t often compare notes, even though that’s primarily what languages are for. How others think of their problems with English can illuminate angles of ours and recast our debates.

That said, this is an extremely fraught post on many levels. At the simplest, though it is about English, even as my first language, I fear my own English is not up to the task of tracing and tying up all the ramifications of the question at hand in under 20,000 words, let alone 2,000. I’ll try and at least flag all issues I cannot address here.

Secondly, this was prompted by a piece about African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Black English. I’m not American and cannot claim any recent African ancestry. And despite being a brown person from a poor country, I don’t find ‘person of color’ a particularly valid locus standi to write and argue from, especially on this question. Instead, I speak as a citizen of the world who cares about inequality deeply and studies it broadly. Even so, when I argued with myself about writing this, I only narrowly overcame an instinctive diffidence because the Times column included a conclusion drawn from the script of a single Hindi film. If 150 minutes of a foreign language film is sufficient to cite in a Times opinion column, I felt I had me some viewing under my belt1, to hold forth on a different dialect of my own language.

Incidentally, it was through John McWhorter that I came to understand inequality of language. That “any vernacular way of speaking is legitimate language”. The fact that I should only properly see this in my twenties was itself a glaring symptom of pervasive inequality.

Which is why it was a surprise to see the recent column where he took exception to some professors who teach English composition suggesting at a conference that native speakers of Black English be allowed to write in their home tongue in college work. His primary argument is that “the notion that Standard English is exterior to Black students’ real selves” is inaccurate. The column brims with rightful pride over a remarkable facultative adaptation.

For most Black Americans, both Black and standard English are part of who we are; our English is, in this sense, larger than many white people’s.

He goes on to cite examples of effortless code-switching (or ‘style shifting’) in the speech of eminent Black authors and their characters. That quote above begins with the qualifier ‘most’, but the article makes no mention of the rest and their interface with college. The effect is to imply that there are no pockets of communities with college aspirants where Black people are not efficient code switchers. Throughout the world, you will find sections of communities that are so marginalized that they have very little contact with better-off people who speak the very different dialect that is deemed the standard. Not enough contact anyway for them to be equally at ease in using that ‘standard’.

McWhorter had some in that group on his mind not long ago. In 2019, he argued for court stenographers to train in the nuances of Black English in a piece titled, ‘Could Black English Mean a Prison Sentence?’ Oddly, there too he repeated the assertion that Black people—implying all of them—juggle effortlessly between Black English and Standard English. But that suggestion goes against the premise of the entire article. If every Black person can effortlessly code-switch to Standard English, why did they not do so on the dock at criminal trials? McWhorter’s account would suggest that they would even when there weren’t substantial costs to not switching. In the criminal justice system, as the title says, the costs are substantial. It stands to reason that some people either cannot switch in the moment, or, even more significantly, feel no need to. If I truly believed my dialect legitimate, I wouldn’t. In the article McWhorter said:

A linguistically sophisticated America would understand that these speech patterns are not a pathology; they are the vessel of as much clarity and nuance as those of a privileged college kid.

Indeed. Why then shield the more privileged college kid, including efficient code-switchers, from critiquing an essay a classmate wrote in Black English?

Every university has a writing program. What is their purpose? Their existence implies that high school graduates have some more learning to do before they reach a proficiency that employers expect from college graduates. If non-Black students too are learning new things and receiving guidance to improve anyway, why not take the opportunity to make the entire class more conversant with a second legitimate English dialect in their country?

Here’s the angle from which I take on this weighty question: if it is legitimate, why is it not standard? ‘Code-switching’ sounds like a bug patch. Why not expand the code? As McWhorter knows far better than I could hope to, what we call standard today was once spoken in some homes in Southeast England. My guess is, right until TV made American idiom more popular in the UK. More popular and rather arbitrarily a ‘standard’ acceptable at college, but not nearly universal. On some of the most popular British TV shows, you can hear lead characters speak in a perfectly accessible alternative grammar that colleges across the Commonwealth still frown upon. (Remember DI Fleming, anyone?)

Even in our times and even in the US, the language of a Times column has steadily moved towards a more conversational style. Whose conversation? It is the style of conversation in some homes. Why not others? Black English has had and continues to exert an outsized influence on art, music, poetry and social media in America and far beyond. Why does its imprint on mainstream news media come in much smaller and sporadic doses? The most popular BBC shows actually offer a surprising hint, but more on that shortly.

Equally puzzling, McWhorter made no response to the people at the conference who, in his selected quotes, conflated non-Black minority students with speakers of Black English. Most non-Black families either speak Standard English or something other than English at home. The question really doesn’t apply to them. Why are academics at a conference confused on this point?!

Which brings me to McWhorter’s chosen examples for cross-border comparison. Despite Line of Duty or the inimitable oeuvre of Clio Barnard, he didn’t go for young students in Belfast or Bradford2, especially the previous generation. He picked examples from Mumbai and Marrakesh.

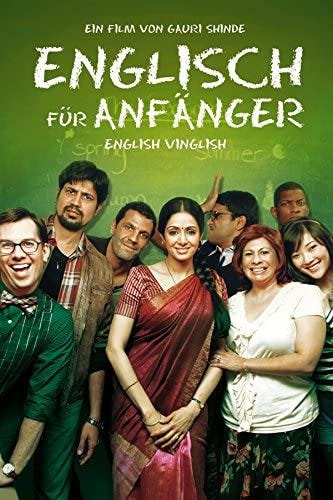

Not long ago, I took in Netflix’s Bollywood romantic comedy “Love Per Square Foot,” in which the characters speak “Hinglish,” a neat blend of English and Hindi... In the movie, there is nary a suggestion that the English feels to the characters like a spritz of cold water on every second sentence from a mustachioed British imperialist.

It is a telling choice. The analogy strains against massive inflation of the subset that cannot code-switch on demand from the minority it might be among Black Americans to the vast majority among Indians. It is one thing to remove a small subset of Black Americans from a conversation on college writing. It is quite a leap to point to a section of privileged Indians in a film to the effect of, “Look at them over there, they don’t seem to feel a colonial burden! Why should we?” Look closer, sahib.

The code-switching in the Hindi film was meant to buttress his argument that Black people can “walk and chew gum at the same time, like countless people around the world—and like it”. People who live in India, if they’re paying attention, know that only those who do it like it. There are countless others around to whom it feels much worse than “a spritz of cold water”. A majority of Indians do not code-switch between English and their first language. I cannot fully convey in my own words what some people across the country have told me the code-switching done in their presence, sometimes ‘for their benefit’, feels like. To paraphrase a young man from rural Himachal, casual English sentences around him are as hourly reminders with verbal lashes: you do not have the means to materially change your station in life. You will forever remain in the background waiting to serve, waiting for them to switch to Hindi to address you to tell you what they need. To anyone who has lived in India more than a few months, it wouldn’t come as a surprise that Hindi is of course not his first language. Hindi is the language he had to get fluent in before leaving his village to seek economic opportunities in the land of the code-switchers. You see, there isn’t much code-switching between Kumauni and English.

This is the place to plant one of those flags I mentioned at the start above—an extremely complex dynamic in a large diverse country, to which I cannot do justice here. To get a sense of the size of the error in the comparison between English divides in the USA and in India, I hope McWhorter’s readers also read Aatish Taseer, Pallavi Aiyar and Jason Gurnebaum. The latter is professor of Hindi, in response to Taseer. (I share them for their description of the problems, not as an endorsement of any implied policy solutions to mitigate them.)

If the sheer statistical difference between Hinglish and Black English was at one end, the comparison to Arabic in North Africa reveals the other end of the scotoma. Even without any experience of the region except a few old classmates, I know that the relationship that native speakers of various Arabic dialects have with the language of the Quran is nothing like that of South Asians or seventh-generation Black Americans with English. For one thing, the broad access to instruction in the standard structures and enunciation of the Quran through religious schools. That said, I wonder if all immigrant workers from the Maghreb in the UAE are such efficient code-switchers that locals in Abu Dhabi find it hard to tell them apart. Do they regularly write op-eds for Al Khaleej? If I were writing about the region in turn for the New York Times, I’d cite an expert on the matter, for one additional reason. At least this comparison was to switching between dialects, you think, unlike Hindi/English. But then their troubled colonial relationship in much of North Africa is with French, not Arabic! This reminds me of a scene from one of my favorite films, Entre les Murs. The banlieue kids, most with North-African ancestry, bristle in indignation at their teacher’s suggestion that they might someday be required to code switch when in genteel (read non-immigrant) company!

I say when examining Black English, let’s resist the flights to South Asia or North Africa. Let’s just look harder at the home of this language of ours. Better than requiring that all Black Americans code-switch just as effortlessly as privileged bilingual Indians, we can liken them to teenagers in England who are not allowed to write the way their parents speak when they reach college. Contrast Americans with British ancestry. You can hear what is called non-standard grammar in Depression-era films like Grapes of Wrath. By the time All in the Family is on TV (1971) you can hear Archie Bunker’s daughter is already shifting away from her parents’ dialect towards more ‘standard’ American English. The facts that on both sides of the Atlantic, some Anglophone communities rapidly assimilate with the dialect deemed standard while others do not tells you there are persistent barriers.

Conversely, US journalists can use Americanisms like ‘swing for the fences’ or describe a person as a ‘rube’ or a ‘hick’, both of which mean a bumpkin. College students can use obscure words of colonial Indian origins in essays because authors have used them in highbrow literature. Standard English can include words no one uses in actual conversation and we’re all expected to either know them or take the trouble to look them up. But English readers must pretend that phrases like “we was”, “her said”, “she done that” or “I saw theirself” are too nonconforming even when their meaning is plain and millions say them everyday! We pride ourselves on a language so welcoming that even indigenous languages that might themselves soon disappear may live on in what we have elevated to everyday words (chocolate, hurricane, barbecue…). Yet in its syntax, English refuses constructs that some English folk use today and have used for centuries!

And hence to the more central question: Why resist the change to a more accommodative standard and instead require those born on the side of an artificial disadvantage to ‘just’ code-switch when we know there are substantial cognitive costs to code-switching?

I think a fundamental tension comes from one’s perspective of what the college writing proposal amounts to. McWhorter feels allowing some students to write in Black English means setting it apart from the Standard. Whereas to me it necessarily means expanding the standard, the idea of a standard, to include Black English. For what is the definition of Standard English, if not ‘that which college professors expect or allow in curricular writing assignments’. It also seems to me that non-switching Black People already treat their dialect as a language standard that others (better) follow. They clearly think the burden of comprehension is on you, as with the woman who said to McWhorter, “Dat table, dey close?”. Because they’re speaking English as it is spoken where they stand and you’ve wandered into that space. (There’s a parallel in Marathi we’ll get to in a minute.) I’ve experienced that firsthand, once browsing at several retail establishments within one block of the White House in DC, every single till ‘manned’ by a Black woman. Don’t you wipe your new glasses on a sleeve… It’s ok you can touch that camera, don’t be shy… You’re not going to have anything solid with that coffee? The folksy version of the taunt — I forget the exact words — always came with a materteral smirk, even though I clearly sounded like I just stepped off a long-haul flight.

Given that my convictions on this derive from career scholarship by him and other experts, the divergence with McWhorter probably just comes down to the more pragmatic aspects of the proposal. Among the people at the conference he quotes, one points out that some of the students whom the proposal hopes to help themselves resist the policy as “setting them up for failure”. Yes, it cannot be a sudden policy change and certainly not at just a handful of universities. If all schools and universities in USA grant Black English the same status as Standard American English in June 2022, the perception of employers will not change within that month. The change needs to bring much of broader society along. It will take time.

There will be a period of transition. In that period, college students may be offered their choice of English on some but not all assignments. Maybe the Times invites Guest Essays from some of the best writers of Black English so readers across the country get used to it. Perhaps CNN and MSNBC stop requiring some people they interview on the ground to code-switch if they find it more natural to not. Gradually, the nation comes around to understanding a language as a collection of mutually intelligible dialects where no one needs to code-switch to suit others.

American linguists have long held out hope for the “linguistically sophisticated America” as McWhorter characterizes it above. Most prominently in the aftermath of a famous 1996 incident that McWhorter mentions, where a school board in Oakland, California proposed to recognize Black English (under a different name) and accommodate it in the curriculum. It stirred up a nation-wide discussion. As Marcyliena Morgan (now at Harvard) put it then:

I now realize that linguists and educators have failed to inform Americans about varieties of English used throughout the country and the link between these dialects and culture, social class, geographic region and identity.

When the US achieves that transition, the group of people most inconvenienced would be people like me, speakers of Standard English outside America, who rely on the UK and US elite to enforce it on all content they produce and make our lives easier. (Part of their incentive is that we offer a large and growing market for that content.) We are not immersed among speakers of Englishes marginalized in their home countries. But we’ll adapt. The way in recent decades citizens of UK grew used to news anchors who didn’t speak in RP, the way I grew used to some aspects of Black English because some of the best TV shows produced in recent years featured it without subtitles. (I may not understand every neologism that young folk come up with, but that’s the same with youth slang in London or Paris or Mumbai. I’m not calling for any of those niche sociolects to appear in college writing either.) When US newspapers allow op-eds and reporting in Black English, it will sometimes be an amusing challenge to figure out what precise tense and subtext is implied. But we’ll have John McWhorter’s books and podcasts to guide us through the tough transition!

Which brings us to what my line of argument means for the other kind of ex-British colony. Is there unifying principle to guide how every English-speaking population determines its relationship to a standard dialect?

I believe any dialect as spoken at home by a significant proportion of the population is equally legitimate, because it becomes the first language of the children from those homes. They shouldn’t have to make concessions for children who come from other homes. It is fairer that each group gets familiar with the other’s dialect and through that, appreciate a fuller, richer, and truer grasp of their own first language.

What proportion is ‘significant’? That is a political question, not simply a linguistic one. But the ends of the range seem clear. Black English is spoken by roughly 10% of the US population. That is well above significant. (By that metric Standard American English wouldn’t expand to assimilate, for instance, Gullah from the southeast coast anytime soon.) In India, by contrast, the fraction of people who exclusively speak Standard Indian English at home is infinitesimal. The vast majority of Indian children who have some contact with English, make that contact at school. If most Indians are receiving English, rather than acquiring it at home, it makes sense for educators all over the country to teach a standard version, which doesn’t have to be either British or American or South African. The picking of a standard is a separate exercise, different in every context. That is another flag though, a thorny question that I cannot cover here— the current status of a standard or a lack thereof in former colonies like India. In Malaysia or Singapore, the reach of Singlish might make it an entirely different question. In urban Kenya a few years ago, it seemed to me Standard English already had much deeper penetration than in India, cutting across class. All of these varying trajectories of the language in individual countries, whether guided or laissez faire, will braid into what might become Standard Global English.

India, though, excels in juxtaposing opposites, as has been said. So if that distant vision of a no-switching future for an accommodating American English in the USA makes you wonder… Is such a world possible?… take the 18th parallel north from Puerto Rico towards the east and keep going until just a little past Mumbai.

In Pune where I live at the moment, several dialects of Marathi mingle in a curious dance of equals, more Troika than Tango. Now, no one I know would suggest that this part of India, unlike the rest, is a haven devoid of other forms of inequality. The dialects themselves map onto divisions of class and caste to some degree and in uneven ways. I should also clarify I am no expert in Maharashtra sociology or Marathi, but this is one of the languages I learned and spoke as a young child. I can tell the dialects apart, certainly the ones I don’t follow. I can report that in some pockets, there is no attempt whatsoever at code-switching despite daily contact.

Most middle-class homes in urban India have hired household help. The workers are often migrants from rural parts, sometimes far away. In Pune, many are from villages nearby. On occasion, I catch bits of conversation between senior citizens and someone who works in their house. Curiosity first lures me into eaves-dropping, if you want to call it that. The women make no attempts to not be heard five meters away. (Gender dynamics means both actual housework and its administration are still mostly the domain of women right across the class divide.) I linger because what follows amuses me. While I can only follow the employer, the two women have no trouble understanding each other. That’s why I’m inclined to think there’s only minimal code-switching going on. The urgent animated conversation fades as I walk past them, leaving me contemplating the phenomenon.

I don’t know exactly how this state of affairs came about. Someday I hope to consult an expert on this3. My guess as to why the code-switching isn’t necessary — usually instituted by the side with privilege — is that the reasons are economic. If you’re in a culture accustomed to help with housework and you don’t wish to pay much above the market rate, you have a strong incentive to learn the dialect that nearly all applicants speak. From frequent arguments I overhear regarding days of leave, I’d wager demand and supply are quite neatly matched. Besides, for egregious socioeconomic reasons, you’re unlikely to find a domestic worker who speaks the same elevated dialect as you. Or perhaps the primary factor is political economy. Much of the area in Pune’s current municipal limits was urbanized relatively recently. Neighborhoods still bear the names of what were probably self-sufficient villages for centuries. Land use changed beneath people’s feet rapidly and dramatically.

I share that extended anecdotal observation only to say that to me it seems — again, a hunch — that asserting their native dialect, not giving in to code-switching, accords speakers of a non-standard dialect the dignity they command more generally. It is not a dignity bestowed, your ties to the land on which you stand immanent in every word you speak. To yield spoken words of their choice is to nod away your tacit approval, so to speak. Consent that in the world as recorded on paper, in the only words that matter — written words — they didn’t need.

I cannot say precisely what the minimal need for or attempt at code-switching in Marathi signifies or if it even is as minimal as I make it sound. At any rate, whether or not a no-switching example exists somewhere in the world is not directly relevant to what English speakers everywhere, UK, India, USA, can aim for. Those of us who believe languages continually change, gather new words and structures, adapt long-held meanings of common words, those of us who accept radical swift changes such as uptalk or SMS syntax and emojis, we could welcome this change as well.

Maybe someday some form of Standard English will emerge as truly universal all on its own. Or it could be the beautifully syncretic creole of Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck’s The Expanse. Whatever it takes, let it not emerge in us policing the use of some dialects in certain spaces and uses.

Post Date

29 July 2022: At least the folks at Oxford Dictionaries seem to be on board. They have collected a whole new dictionary’s worth of usage. Said Sonja Lanehart, a member of the advisory board on the project:

It is almost never the case that African American English is recognized as even legitimate, much less ‘good’ or something to be lauded,” she said. “And yet it is the lexicon, it is the vocabulary that is the most imitated and celebrated…"

A small selection of screened stories led by a Black cast that I have relished just in recent years — One Night in Miami, Atlanta, Watchmen, Moonlight, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Judas and the Black Messiah, Empire, Roots, The Underground Railroad, Lovecraft Country, When They See Us, If Beale Street Could Talk, Nope, and South Side. Though he doesn’t mention it there, John McWhorter must have a similar list of films in the many languages of South Asia hopefully including the recent Fandry, Mandela, Newton, The Disciple, and the older Manthan, Garam Hava, Mirch Masala, Masoom, and Rudali. Not much English in them of course.

I mean, how long back did multiple dialects coexist in a radius of 50 Km around Pune? Which of them arose or arrived here last?