Having children and having - part 2

For couples with moral doubts about raising a family in the backdrop of climate change, two New York Times columns took a blinkered American view to allay fears about a global problem.

Picking up from the last post on abortion polemics, this one is on almost the reverse question upstream. Not what to do when you’re pregnant with a child you did not elect to have, but whether to elect to have children at all. As it happens, both Ross Douthat and Ezra Klein, soon after tracing arguments on the first question, visited the second.

Maybe this time I should just start by assuring you that I do not have an unhealthy obsession with either writer. I do read other columnists, including in other outlets. The reason you find this newsletter regularly returns to the words of Messrs. Douthat & Klein is that in my estimation, they have a consistent record of lucid and thorough arguments. I admit to immense envy at their composition and rhetorical skill.

Douthat, as I’ve said, is all the more remarkable because I don’t agree with him on much and his columns rarely bring me around to his view, but he does a great job of explaining all the valid thought threads of the people I disagree with. In a strand of ancient South Asian philosophy, the art of argumentation begins with पूर्व पक्ष (purva paksha). That is Sanskrit for a custom to demonstrate ‘prior facility with the other side’. A good debater in an ideal debate will begin by explaining in good faith what the opposing side believes in a thorough and fair manner. That is what Ross Douthat offers me.

It is quite a challenge to find blind-spots in their reasoning, which makes such finds more worth writing about. The fact that their columns often veer into overlapping territories in not really a coincidence given what their work is and where they work.

So anyway, though Douthat is the social conservative who believes Christians should raise large families, it was Klein who first sought to reassure Times readers who express doubts about swapping the condoms in their regular Amazon carts for diapers. Many readers ask his opinion on whether it is morally right to have children given the environmental catastrophes that await them and those children’s role in potentially accelerating them.

The first rationale Klein chose to argue that they take the plunge, so to speak, was to point to how previous generations had children in times when they too feared grim futures.

To bring a child into this world has always been an act of hope. The past was its own parade of horrors. The best estimates we have suggest that across most of human history, 27 percent of infants didn’t survive their first year and 47 percent of people died before puberty.

I was not sure of the thrust of this. If the point is ‘life was worse in the past’ or ‘prospects for babies were bad then too’, a long list of criteria can help you make it. Picking child mortality as the only indicator of comment is an odd choice. Of all the indicators of dismal life, these two specifically compel society to have more children, just to sustain itself. If we have since improved on those two indicators, it’s a sign we’re now less obliged!

But let’s address that angle anyway. People in the past had children even when prospects for those who would survive into adulthood were not great. He cited Dylan Matthews from Vox:

What today we’d characterize as extreme poverty was until a few centuries ago the condition of almost every human on earth. In 1820, some 94 percent of humans lived on less than $2 a day. Over the next two centuries, extreme poverty fell dramatically; in 2018, the World Bank estimated that 8.6 percent of people lived on less than $1.90 a day. And the gains were not solely economic. Before 1800, average life spans didn’t exceed 40 years anywhere in the world. Today, the average human life expectancy is more like 73.

Matthews linked back to Our World in Data. Beside the graphic, the original authors repeatedly caution against using the meticulously collected data from the 19th century in a single paper to infer anything in terms of quality of life in objective and relative terms. They don’t give detailed reasons there but there are several.

Even though the ‘$2 a day’ you see above is adjusted for inflation and prices, it imposes 2002’s values of what people ‘need’ on people who lived in 1820. It is a failure to truly put yourself in the milieu you wish to judge, which for many in the US and EU needs a fertile imagination. In India, on the other hand, I live amid constant reminders that what people need and want is highly subjective — it is determined by culture, values and what you personally believe a good life needs. On the other hand, many in India lack some of the same things that many in 1820s USA wanted but did not have — adequate sanitation, for one. What is more, the likelihood of those Indians getting a lot of what they do want is somewhat contingent on the lifestyle emissions of new babies born in the USA today (much more on that below).

Secondly, time. When average life spans were 40, what proportion of people had to spend 50 hours a week or more on hard work plus a commute just to make ends meet? What proportion had to spend at least 12 years fulltime in education to even have a shot at joining that daily grind?

The somewhat vacuous ‘living standards’ comparison across centuries is something my fellow economists came up with to answer the quibbling critique that capitalism seems to both require and (hence) perpetuate inequality visibly in our lifetimes. Yes, aristocrats died from minor diseases that can today be cured with antibiotics available to billions over the counter (but still not to everyone). I have not seen any of these economists administer a survey to a significant sample from the poorest billion today and ask them if they’d rather live the shorter life of an aristocrat back in the 1800s.

Or the reverse. Imagine a British aristocrat from your favorite period TV drama whom you manage to befriend and introduce to one of the people on those data charts who’s been lifted just above extreme poverty in recent years. If you offer them to trade places with an Indian factory worker in 2018, do you think they’ll jump at the chance?1

Let me again clearly state, just like liberal democracy in a previous post, I do believe in functioning capitalism as it serves society better than alternatives. But it can function much, much better. And the talk of incommensurable metrics like lifespans in the Middle Ages is a distraction from all we need to do today to guarantee a really free and fair market even to firms today, let alone to people globally. In the current context, that trope is doing an even greater disservice in reducing planet-threatening changes to something more akin to timeless human hardship.

Klein went on:

No mainstream climate models suggest a return to a world as bad as the one we had in 1950, to say nothing of 1150.

The fall in extreme poverty since the 1950s is much more real and meaningful. But as for returning to a world ‘as bad as 1950’, Klein apparently means climate change will not cut average American incomes down to 1950s level. Not the average, not Americans no, but what about those for whom it will hurt already low incomes? There are people in Asia and elsewhere whose real incomes will start falling after having seen only a decade or two of modest growth. And income aside, what about all the other hardship climate change is absolutely certain to inflict in a 2022 newborn’s lifetime? The need to give up agriculture as a source of livelihood. The physical displacement to who knows where. The political vilifying by natives in your new home, which would itself be reeling under the vagaries of extreme weather.

The 1950s were experienced very differently around the world, but when in the last century were so many uprooted from the only life they knew all over the globe at once? To properly weigh the moral decision to procreate today compared to our ancestors: When in the past did we know we had been directly responsible for nudging the planet irreversibly towards tipping points? Was there ever a time when young families knew that major cities or settlements are going to disappear or become unlivable in the lifetimes that begin now?

The moral side of the question really opens up wide if you allow a truly global conversation, even if you’re concerned only with American pregnancies. But even with hard numbers available, the Times looked only at a fraction of all that is relevant. Quoting a scientist from the University of California, Klein went on:

“The goal is to undo that structure so children can be born into a society that is not putting out carbon pollution. That’s the project.”

And it is a doable one. Per capita carbon emissions in the United States fell from more than 22.2 tons in 1973 to 14.2 tons in 2020. And it can fall much farther. Germans emitted 7.7 tons of carbon per person in 2020. Swedes emitted 3.8 tons. “In a net-zero world, nobody has a carbon footprint, and we could stop tabulating guilt by counting babies,” Wallace-Wells told me.

I’m so glad 26-year-old me at the International Institute for Industrial and Environmental Economics in Sweden in the mid 2000s does not know we are citing emission figures that way in 2022. After decades of feet-dragging by governments, some of it spent arguing with a diminishing body of deniers, with near consensus on the physical facts of warming, after eight seasons of Game of Thrones tried to hammer home the nature of global problems, the New York Times (alongside peerless climate coverage in other sections) continues to fail its readers in explaining the economic hard realities of climate change and environmental problems.

That quote above, maybe unwittingly, switches the frame when you’re not looking. Sandwiched between the ‘not putting out carbon’ and ‘nobody has a carbon footprint’ are quantities for emissions from production physically within these countries. Even though at the source they link to, Max Rosser and Hannah Ritchie took great care to caution that that is an undercounting. Better numbers appear on the same page under the head of Consumption-based Accounting. Put simply, wealthier countries tend to consume many goods that have done most of their carbon emitting when being produced in a poorer country. Our World in Data goes into the details on a separate page.

On either of those pages, it is clear that accounting for total consumption including imports, Europe actually looks worse than the US, undercutting the point Klein seemed to want to make about evident potential for the US to improve.

Bringing up global emissions inequality, I risk invoking the specter of “Western guilt”, hinted in that quote above, which Douthat voiced more explicitly in a quick follow-up column in support of Klein’s.

Guilt looks at the past. The way I see it, those who ask themselves the question in earnest, in USA or elsewhere, have their eyes to the future. Note that though I feel it is directly relevant to agreements between world leaders on climate change policy, I do not bring up historical emissions (before 1950s). This post only covers the facts on the situation at present, because even those are rarely aired in full.

I do not hold that parents in rich countries should forgo the joys of parenting simply out of guilt. If in weighing their moral qualms, after they consider all facts, they decide to have children, I send best wishes to each child. The twin columns by Klein and Douthat did not exhaust all facts. Even in restricting itself to only the present, the Times presented a small fraction of the global picture.

The pollution inequality that maps onto global income inequality is of course much greater than reflected in greenhouse gases (GHGs). But before I get into the hard numbers on what are called ‘embedded emissions’, a brief tangent for a quick primer. If you are very familiar with the technical aspects of environmental economics, please just skip to the next heading for the data.

Brief Explainer

This should have been an easy post to research. I studied environmental policy before moving to economics and embedded emissions, at the intersection, have long been a personal bugbear. But the magnitude of two values in conflict makes it difficult to lay it all out. Trade bestows enormous benefits but exacts enormous hidden costs, both unevenly borne across and within countries.

On the one hand, it is not just modern mathematic models that tell us trade is inevitable, efficient and smart. Evolutionary ecology and paleoanthropology indicate organizing human societies without trade is almost a contradiction in terms.

But trade was more straightforward and economically more ‘efficient’ when one tribe was trading sharp obsidian arrowheads with another just across a river or a mountain that specialized in making wooden shafts. Every so often, representatives would meet at the border, exchange heads for shafts, and go back to their camp to assemble arrows which with to shoot any trespassers from the other tribe outside the seasonal trading window. That is also what a lot of international trade looks like today. (Remember that American company in Russia supplying material to Russian weapon manufacturers.)

Then, as we multiplied and migrated to occupy all corners on every continent, we effectively veiled some of the ‘market failures’ that on a local scale are only too well understood. Pollution is a known market failure, but it belongs to wider category that economists call ‘externalities’.

All economic activities have associated externalities — effects that are not priced within the market. That is, they are external to the market. The acts of producing or selling anything results in some byproducts that your neighbors may not want near them. You earn a profit from selling what you sell, but your neighbors never get directly compensated for the noise or smell or toxins that your business is emitting. This was an old problem that law tried to address and the mechanisms are still the basis of much environmental regulation worldwide. Worldwide, but for local regulation. That is, when the business of one person is a nuisance (that’s the actual legal word) to another in the same tribe.

Back when tribes were trading across a river, you imagine they were very familiar with negative externalities of whatever activity the other tribe specialized in, so they would accept the price with those costs factored in. Both parties entered transactions in possession of full information.

To weigh against all its enormous benefits then, one downside of global trade is the mental distance it puts between the consumer and the impacts of their consumption.

The data

At the current time, Our World in Data does not seem to have data on embedded emissions other than GHGs. Climate change is one of many environmental problems. Global data on other emissions is harder to find.

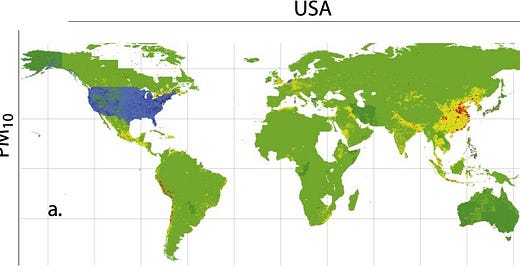

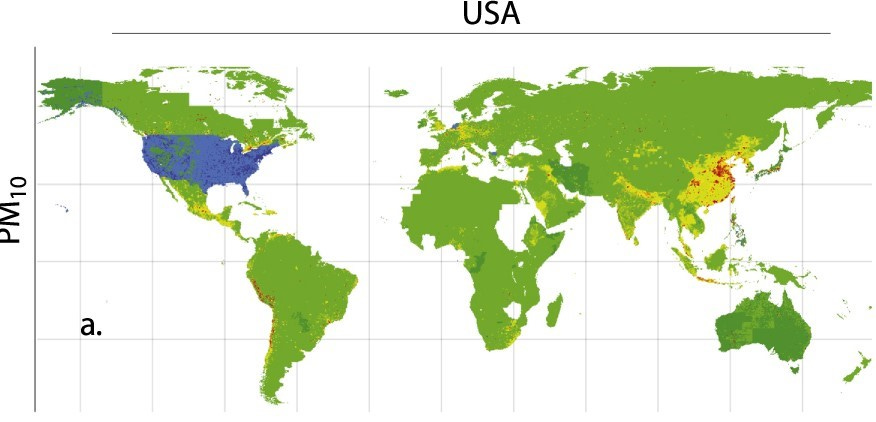

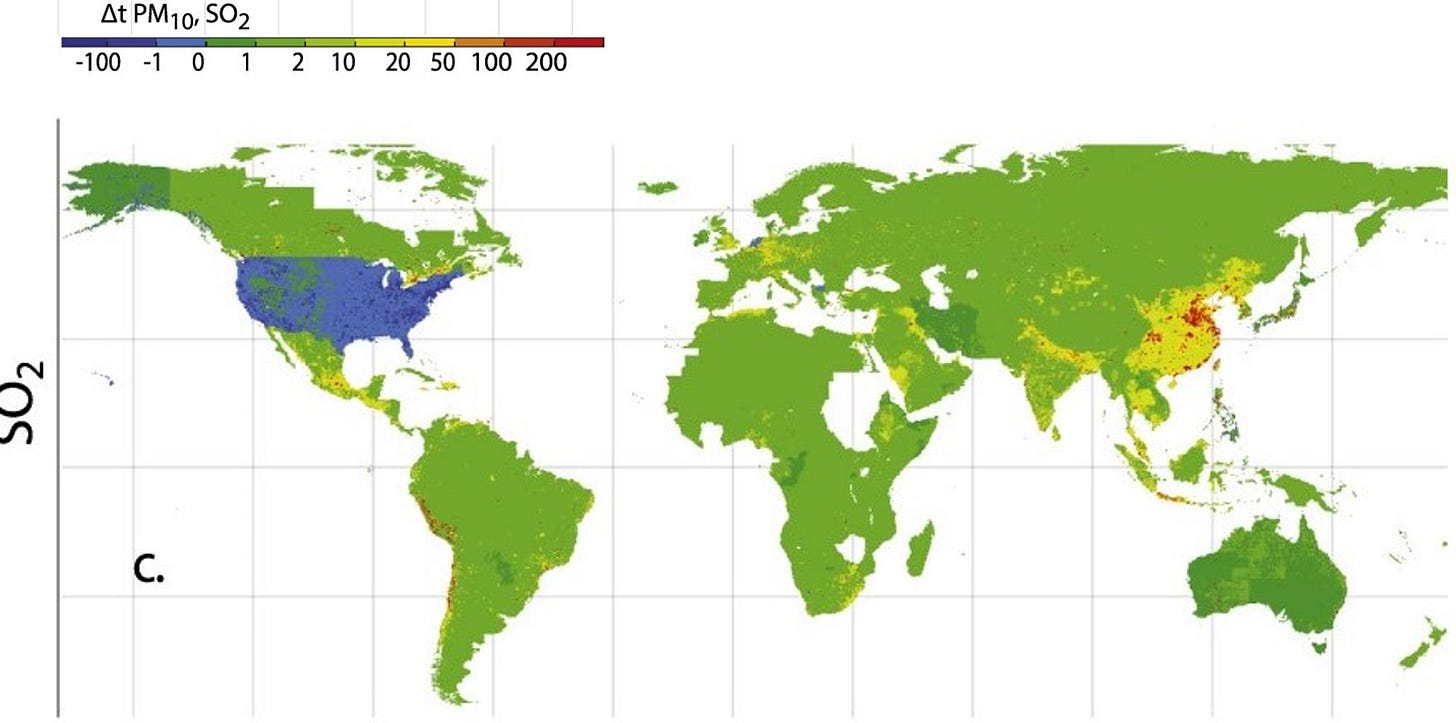

For years, Daniel Moran and Keiichiro Kanemoto have been hard at work producing maps like the ones below that show in a simple visual who is directly affecting whom.

Blue and purple indicate locations from where emissions caused by things Americans buy have moved away. Yellow through red indicate the locations to where those emissions from continued American consumption have moved. From 1970s onwards, Americans have enjoyed cleaner air not primarily because their lifestyles got cleaner, but because they have been increasingly buying things that emit the same pollutants all over China, India and Mexico instead. The European picture, not included in the paper, would be similar.

A narrative

Even the Americans and Europeans who are aware of the direct harm from pollution their lifestyles cause might have mixed ideas about why so much of the pollution from things they buy everyday harms people they rarely think of and know little about.

Let’s use a thought experiment, not dissimilar to the sort that I belittled in the context of part 1, but a bit less hypothetical. A very well-off person, Andrew, and a much poorer person, Barkha, meet in a market. Andrew is there to buy a product and Barkha to sell something she made. She makes the product right next to her little straw hut, exposing herself and her children directly to sickening pollution. Also in the market is a second seller, Chang. He produces the same product at a facility a little distance away from his children. And he uses a technology that minimizes direct health effects on him, which, while lower than in Barkha’s case, are nonetheless significant. His price is obviously substantially higher. At ‘current best technology’ (another legal phrase), it is impossible to make this product without any pollution at all, which is partly why Andrew is in the market to buy it, rather than getting a neighbor to make it. (For reasons we just saw. The neighbor would be his own ‘tribe’, a name easier for him to pronounce. Same jurisdiction.) All three are aware of all the facts of the case in this paragraph. Andrew’s employer has not given him a raise for five years in a row. Given the prices, Andrew naturally chooses to buy it from Barkha.

Who is to blame how much for the health effects on her children?

The difference of that imagined market with the real world is mainly in the information that parties have. We said all three have all the information, but of course they are proxies for governments. In the real world, Barkha, given her station in life, may not be fully aware of all the harmful effects of pollution on her family. Her government would likely know more. From her government’s point of view, raising regulatory standards on the industry would mean losing global competitiveness. Their market share would immediately contract. Far worse than slow health effects, Barkha (standing in for a large number of producers) would suddenly have no income.

The choice that her government has is not quite as simple as between regulating industry (within the resources of a poor country) and ignoring the health of its citizens. To set up regulation in a way that minimizes the economic damage from lost trade, a majority of the countries on the global market would have to cooperate (the way EU members uniquely do) to set minimum standards. Prices of everyday commodities would of course rise immediately. With inflation where it stands, mid-2022 is actually a good time for readers in the US and the EU to reflect on how eager they feel to support their own governments in standardizing regulation2 of manufacturing industry some day soon.

And that was still just pollutants to the air. Emissions of other pollutants — heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, plastics, endocrine disruptors and other chemicals are also skewed due to trade. And finally, there is habitat loss. This was again the subject of a map that Daniel Moran and Keiichiro Kanemoto managed to find the data to make. The Times ran their world map of biodiversity impacts of goods consumed in the USA in 2017.

If climate change has prospective parents in the rich world asking themselves the moral implication of procreating, how would a more complete acquaintance with the full platter of pollutants emitted by a North-Atlantic lifestyle and their impacts affect their decision?

Back to climate

GHGs get so more more press than all those other pollutants partly because the latter’s effects are localized. Climate change is a global problem that affects everyone everywhere, but even its localized effects are much larger in magnitude. But above all, its drivers are designed deep into the systemic masterplan of all human economic activity. Even among Times pundits, few recognize the scale of the modern world’s entanglement with fossil fuels. Klein said:

We face a political problem of politics, not a physics problem.

Describing it as primarily a political problem casts those who are conservative on climate change regulation in maleficent roles. The problem is economic first. For a one-stop satellite-view lesson, one need look no further than Vaclav Smil’s latest, which the Times also reviewed.

For all the progress that the internet age has created on the surface, the global economy and every country that participates continues to be embedded in a superstructure built on four materials — steel, ammonia, cement and plastics. Even if we assume a world where all electricity were green, we do not have ways of producing those four at the scale we need with electricity alone. Since they are such stable bankrollers of the fossil fuel paradigm, we delude ourselves if we think we will stop emitting carbon anytime soon, marquee corporate pledges notwithstanding.

The limits to substitutability between electricity and extracted hydrocarbons is starkly manifest more than before in 2022 in another way. Winter is coming, to borrow a phrase. Even in the richest countries in the world where winters happen to be harshest, citizens might have to “choose between heating and eating”, as the British press puts it.

Those headlines actually allow us to circle back a bit in the conversation. If sharing maps to highlight the scale of horrendous impacts on distant foreigners strikes American voters as rubbing in ‘guilt’, climate change is serious enough that it offers politicians talking points anchored closer home. Last year, over a thousand Americans and Canadians died from the June heat wave, not to count the death tolls of now-regular wildfires or floods in North America and Europe. (Growing meticulous research now attributes most of these events to climate change.) Twenty-first century deaths in a heatwave are not the same as deaths from a medieval plague. Again, morally comparing reproductive decisions today with those of our ancestors, when in the past did we know that what we consume and how much will kill many of our own compatriots?

I absolutely support Klein’s spirit of tempering doom-and-gloom reporting to make room for hopeful information that spurs teenagers into STEM or Mass Communication or other fields of their choice to innovate towards the new world the families they raise will need to reimagine. That is several steps removed from resolving all of the complex moral calculus above in a way that is sufficient to exhort millennials and Gen Z to ‘go forth and multiply’.

The connection between part 1 and part 2 of this post in fact goes beyond the symmetry in the ethical questions at heart. There is some overlap in some of the moral reasoning invoked too.

In several discussions even apart from the ones covered in part 1, Ezra Klein has cited parents who make the difficult decision to terminate an accidental pregnancy in the interest of providing for children they do have. If that makes economic sense for a family with limited means, does it not for wider society?

A world where fertility rates drop below replacement levels for a few decades isn’t some dystopian world where there are no children anymore. There will be fewer children, who we can expect to be happier and better looked-after.

Yes, the global human population will shrink. For millions of other species, that will be great news. If they had words, collectively, they’d chime, ‘’Oh, they decided to live up to the Latin name they gave themselves!” Economic effects on countries could be mitigated by a gradual migration out from regions with lower incomes and dirtier industries to those with higher incomes in cleaner industries. (On migration, there is a lot to say that isn’t often said. I’m sure the Times will give me another occasion to comment on it.)

Douthat ended with:

…the promise of a purposive, divinely created universe — in which, I would stress, it remains more than reasonable to believe — is that life is worth living and worth conceiving even if the worst happens, the crisis comes, the hope of progress fails.

The child who lives to see the green future is infinitely valuable; so is the child who lives to see the apocalypse. For us, there is only the duty to give that child its chance to join the story; its destiny belongs to God.

That link is to a column I’ve responded to before in part, but have not yet completed the response so I will add more on the religion aspect there. To the extent that it implies that everyone who is biologically capable has a duty to reproduce, including those who personally lack the temperament to lovingly raise children, I strongly reject the idea.

We will be 8 billion within this year. Short of requiring a government-issued license, I think it is time that people of all stripes subjected themselves and their partners to rigorous psychological self-scrutiny as to long-term suitability for caring at least 16 years non-stop, devotedly and, within reasonable constraints, selflessly. That belief is unrelated to the natural environment, but I was thrilled to hear an assortment of Indians asking it of themselves in this BBC video below3.

More to the current point, leaving it to God is to treat the question of having children as entirely removed from the question of having. I believe it isn’t. As we saw, whether you ought to have children is tied to what you would like the children to have — both, the children you would have and the children being raised far away. It is also tied to what apart from children you want to have, and not only in the broader sense that Ann Mary Slaughter meant it. In the more immediate and tangible sense, everything we have and next want to have leaves the planet a little more depleted — for the children who have less today, the children who will have less available to want tomorrow and for all the species that ‘have’ nothing and ‘want’ nothing in our material commercial sense. Those three constituencies have no voice in North-Atlantic elections. Like the subject of part 1, this too should be a question of intense discussion. Except it has to be a discussion at the international level and with all the evidence entered, which in case of part 2, is plain.

Post Date

20 August 2022: Regarding optimism predicated on technologies that don’t yet exist, Scientific American has a new article.

16 September 2022: On the economic hurdles to low-carbon transition, NYT has since published new columns. By Thomas Friedman, and by Klein himself, besides all the regular work from David Wallace-Wells.

16 September 2022: William MacAskill’s new book, which I mentioned here last month, touches upon some of the moral questions that attend the decision to have children, including after having them.

I’ll share my answer. For the best-managed factories in either China, India or the USA, the answer is an enthusiastic ‘yes’. For the worst-managed factories in those countries, I’d interrupt before you finish the question, stammering ‘no’ through a shudder.

Existing WTO provisions allow for this to an extent and the EU, to its credit, has regulation that uses them to minimize its footprint. But that footprint remains substantial. Remember current best (economically viable) technology doesn’t allow production with zero pollution.

The soon-to-be world’s most populous country also has a growing movement of more radical believers and anti-Natalists.